In 1911, a group of Chief Petty

Officers of the United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet entered a float in the

Washington’s Birthday floral parade in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The float featured a group of people on

“The Water Wagon.”

The float was a live-action

illustration of the

idiom “on the Water Wagon,” meaning to abstain from alcohol; the original

form of the modern idiom, “on the wagon,” meaning to abstain from alcohol,

drugs, or anything else. The float was

also politically relevant, as the temperance movement was in full swing, with

prohibition and the Eighteenth Amendment just a few years in the future.

A boy/man with a large head and

exaggerated ears could be seen perched at the back of the Water Wagon.

Wait, what? Is that Alfred E. Neuman? Fifty years before Mad Magazine?

Mad Magazine borrowed its enigmatic,

red-haired mascot from a postcard in the 1950s.

The postcard, in turn, descended from

a long line of precursors . . .

. . . all of which stole directly from

Harry Stuff’s 1914 poster “The Eternal Optimist,” which also bore the caption, “Me

– worry?” a precursor to Alfred E. Neuman’s catch-phrase and a reflection of

the “I should worry!” craze that swept the United States for several years beginning

in about 1910.

Harry Stuff’s poster may have been

inspired by a decades-old advertising image usually used to promote “painless”

dentistry.

Those advertising images all trace

their origin to a playbill for the 1895 stage play “The New Boy.”

Like Harry Stuff’s poster and Alfred

E. Neuman, the poster featured a two-part, noncommital catch-phrase, “What’s

the good of anything? Nothing!” suggesting, perhaps, that Stuff may have been

familiar with the original.

|

| Based on an image from, NYPL Digital Archive. |

(For a more comprehensive history of the Alfred E. Neuman image,

If Harry Stuff’s “Me – worry?”

caption was influenced by the original, it was also influenced by the popular

slang phrase of the day, “I should worry,” meaning more or less that the

speaker has nothing to worry about.

(For more on the "I should worry!" craze, see my earlier post,

Surprisingly, perhaps, Harry Stuff’s

poster was not the first “New Boy”-like image with a worry-related

caption. It was beaten to the punch by

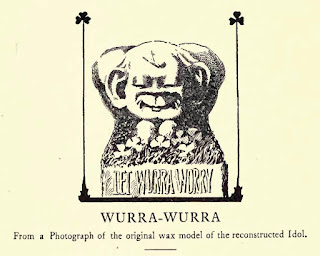

three years by a mock-Irish pagan idol, Wurra

Wurra, whose name is a pun conflating the ancient Irish expression of grief, “Wirra Wirra” (sometimes spelled “Wurra Wurra”) with “Worry Worry” as spoken with an Irish

accent. “Wirra Wirra” is believed to be Gaelic for “Mary Mary.”

|

| Eugene O'Growney, Simple Lessons in Irish, Dublin, Gaelic League, Part II, page 16, 1897. |

It’s not an exact match. The ears are too big, and it’s missing the

gap-toothed smile, but its similarity combined with its worry-related

catch-phrase, make it an interesting cousin of Alfred E. Neuman, if not a

direct ancestor.

But regardless of its relation to the

“New Boy” and the painless dentistry ads, Wurra

Wurra was also a direct knock-off of an earlier, more successful mock-god –

the Billiken.

The Billiken et al.

In 1908, Florence Pretz of Kansas

City created a small statuette she called the Billiken. She also developed

a mock-religion based on “worship” of lucky Billiken

idols; with Billiken as “the god of

things as they ought to be.” Billiken caught the fancy of the public,

and she and her business partners sold millions of the idols and separate

display stands; proof positive that Billiken

was a bringer of good luck.

Good luck, maybe, but not for long.

To Miss Pretz they mean $30 a

month royalty while thousands go to the bank accounts of the men who have

involved the designer in a maze of technically worded contracts and agreements

not understood when she signed them.

Iron County Register (Oronton, Missouri), December 2, 1909, page 7.

Although the fad has long since passed,

the Church of Good Luck and Museum of

Good Luck still

preach the gospel of Billiken online

from their home base in Illinois. See

their website for Billiken

images, Billiken lore and Billiken history.

The success of the Billiken inspired imitators.

In Paris, France, someone created a

“Billiken” of Wilbur Wright.

Wilkes-Barre Times Leader (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), December 2, 1908, page 2.

In London, England, the American

artist Mrs. Bert Longworth (whose replica of the Sphinx was praised by Rodin)

created and marketed a statuette of Solomon.

Solomon

Is Newest “Billiken”

“SOLOMON”

LATEST FREAK

SUCCEEDS

BILLIKEN CRAZE

American Woman Sculptor Chisels

Odd Statuette Which Offers Many Phases, Seeming to Exude Wisdom From All Angles

London, Jan. 21. The reign of

the Teddy bear is over and gone in London, Billiken, that pestiferous little

reminder of things as they are, and his brother, whose apelike grimace is

supposed to suggest the god of things as they ought to be, are alike hurled

from the precarious pedestal of public favor.

Another American “freak,” Solomon, has taken their place. . . . Every paper has printed his picture, every

bric-a-brac shop and every department store is crowded with his haunting

shape. So far as Londoners achieve a

“rage,” Solomon has become the rage of the present.

The Indianapolis Star, January 22, 1911, page 15.

|

| Solomon,

The Star Press

(Muncie, Indiana), January 22, 1911, page 24.

|

In St. Louis, Missouri, someone came

up with a bad luck idol – Jinx – based on a newspaper cartoon strip of the same

name; kinda like a top-hatted Homer Simpson.

Jinx has taken his place beside

Billiken.

The little god of things as

they ought not to be has been done in plaster by a St. Louis sculptor, and for

a very moderate price any St. Louisan can now have Jinx on his desk or his

parlor mantle, or in his garage.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 29, 1911, page 3.

In 1916, someone tried to recreate the Billiken craze, with a new-and-improved "deity."

Will "Nock Wood" succeed Billikin and Kewpie dolls in popular favor? Copyrights on the designs have been applied for. Dealers assert that the ideas of the flowery kingdoms will prevail this season in images and good-luck emblems.

"Nock Wood" is the latest of the heathen good-luck deities to be invented. He is carved out of wood and sits in a posture much like that of the Chinese buddhas. His left hand is to his head in a position of rapping it.

The idea of the inventor seems to be that the old superstition of knocking wood to prevent ill luck is one worthy of being revived. With his invention all one needs to do is to set "Nock Wood" up on one's mantel and let him take care of all the bad luck that is coming one's way.

Dayton Daily News, (Dayton, Ohio), March 26, 1916, page 33.

And in New York City, an Irish-American

publishing house created a new mythological pagan idol intended to ease one’s

worries. The idol took its name from a

long-standing phonetic representation of “worry, worry,” as spoken with an

Irish accent. For example:

“Yis, yis, yer ‘anner. What’ll I do? Och wurra,

wurra! Me husband’s tuk bad, sir, wid the fayver and I’m afeerd I’ll

lose him.

[“Yes, yes, your honor.

What’ll I do? Oh worry, worry!

My husband has taken ill, sir, with the fever and I am afraid that I

will lose him.]

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 13, 1849, page 1.

Wurra Wurra

In March 1911, Desmond Fitz Gerald published

the book, Wurra-Wurra; A Legend of Saint

Patrick at Tara. The Wurra-Wurra of

the title referred to the name of the supposed last pagan idol destroyed by St.

Patrick during the Christianization of Ireland.

The booked appears to have been designed to imbue the Wurra-Wurra idol with some vague,

mystical significance, as was the case with the Billiken. Instead of bringing

good luck, however, the Wurra-Wurra,

like Jesus suffering for our sins, was said to ease worries by taking them on

himself.

Presumably, Fitz Gerald intended for

the book to create a market for his Billiken-like

statuette of Wurra Wurra.

The statuette bore an inscription on

its base – “Let Wurra Worry!”

The ears, teeth and proportions

appear similar to the head riding at the back of the “Water Wagon” in Honolulu

in 1911.

It’s not a perfect match. The eyes seem different. Is it a Wurra-Wurra

that differs slightly from the illustrations, or something else entirely? Perhaps it was an old “Yellow Kid,” a

newspaper cartoon character who enjoyed a period of overwhelming popularity a

decade earlier?

Like a Mad Magazine movie parody, Wurra-Wurra;

A Legend of Saint Patrick at Tara is a send-up of a pre-existing story, in this case the legend of St.

Patrick in Ireland.

As the book opens, St. Patrick destroys

“Cromm Cruach and the twelve smaller idols.”

But whereas Irish legend holds that Crom Cruach was the last pagan idol in Ireland, the destruction of which

cleared the way for Christianity, this

story imagines (like Star Wars Episode V) that there "is another" (although this time more Yoda than

Leia) – Wurra-Wurra.

Let Wurra Worry

[T]he face and figure of the

idol, an’ his wide opin ears foriver listenin’, themselves told the whole story

– not only that it was his business to bear all the worries and troubles of the

world, but that he liked the job!

In the aftermath of the destruction

of Cromm Cruach, according to the new story, Keth, one of St. Patrick’s

Christian enforcers, is dismayed to learn that one of St. Patrick’s

seamstresses, “Finola of the White Shoulders,” was an adherent of the cult of

Wurra-Wurra. He asks her about it, she

confides in him, he falls in love with her, and they go off to see the

Wurra-Wurra.

To make a short story even shorter,

St. Patrick decides that the idol should be saved, but word reaches Keth after

he destroyed the idol (all but one of its ears) during a confrontation with a

wizard. To prevent Finola and other

worshipers from discovering the destruction and taking their anger out on him, he

places his head on the pedestal where Wurra-Wurra’s head should be,

miraculously fooling them into confessing their worries to him. As a result, he inadvertently learns that

Finola returns his feelings of love, they get married and live happily ever

after.

I Should Worry

Wurra-Wurra may

have been inspired by the Billiken,

but it also capitalized on the then-current slang phrase craze, “I should

worry!”

The earliest unambiguous example I

could find in print is from an advertisement for a comedian in 1910, although

it is unclear whether he popularized the expression or merely reflected a trend

that was already underway.

The expression may have been current

before it was incorporated into Peterson’s act, but searches are complicated by

the fact that people routinely used “should worry” in its conventional, literal

sense. If you find any earlier examples,

please let me know.

“I should worry” shows up in print a

few times in 1911, and exploded into a full-blown craze by 1912.

It was still going strong in 1913 . .

.

I should worry,

I should fret,

I should marry a suffraget!

|

I should

worry,

and lose

my goat,

But

nevertheless we’re getting the vote!

|

Evansville Press (Indiana), June 28, 1913, page 2.

. . . although many people were

already getting annoyed.

I’m a peace-loving, diffident,

mild little guy . . . . But rage stirs

my system and wrath sweeps me o’er, a frenzy of fury doth set me afire; I chew

all my nails – oh, I’m terribly sore and, in fact, I’m consumed with

considerable ire when some ivory-beaned boob with a mental snow flurry pulls

that odious, sickening phrase, “I should worry.”

The Daily Missoulian (Missoua, Montana), May 24, 1913, page 10.

Today

Alfred

E. Neuman is the only

reminder of “The New Boy” of 1895 . . .

Note: updated June 16, 2022, to add the item about "Nock Wood."